On January 7, 2019, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) issued two new guidances setting forth revised procedures for examining patent applications. These procedures apply to all patent applications, regardless of when they were filed.

The Section 101 Guidance

The first is under 35 U.S.C. § 101 (Section 101 Guidance) and pertains to what constitutes patent-eligible subject matter. As the Section 101 Guidance acknowledges, consistent application of the U.S. Supreme Court’s framework for evaluating patent eligibility (i.e., the framework established under Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 573 U.S. 208, 217-218 (2014), Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66 (2012) and subsequent cases) by the USPTO’s more than 8,500 examiners across various art units and technology fields has proven difficult. In an effort to increase consistency, the USPTO issued its Section 101 Guidance.1

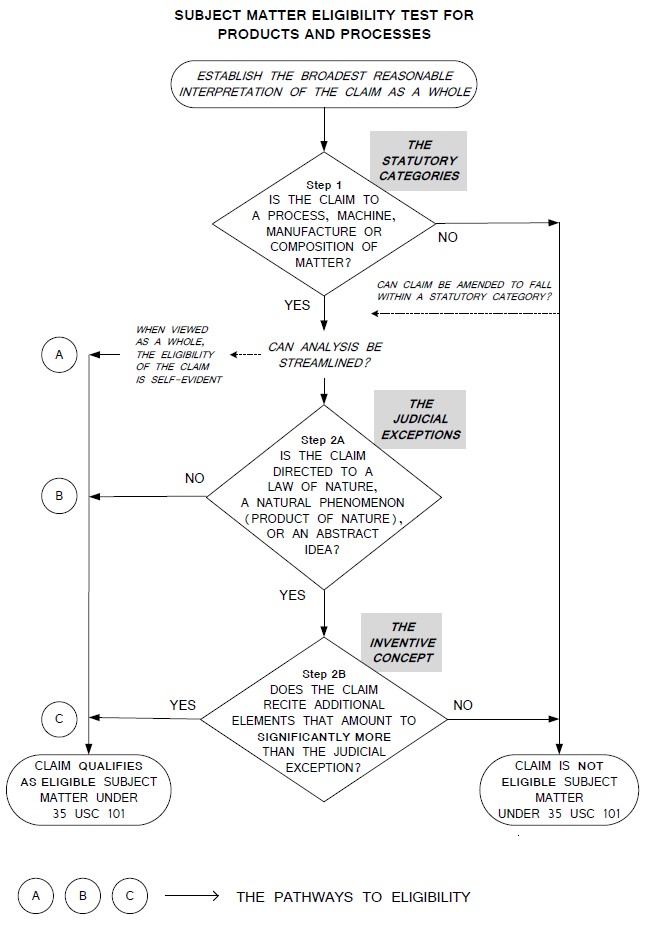

The USPTO incorporated previous guidances concerning Section 101 into Section 2106 of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP), which includes the following flow chart:

MPEP § 2106.

The Section 101 Guidance revises the procedures set forth in MPEP 2106 in two significant ways: (1) the identification of abstract ideas; and (2) the determination of whether a claim is directed to a judicial exception.

Abstract Ideas

First, the guidance “extracts and synthesizes key concepts identified by the courts as abstract ideas to explain that the abstract idea exception includes the following groupings of subject matter”:

Mathematical concepts — mathematical relationships, mathematical formulas or equations, mathematical calculations;

Certain methods of organizing human activity — fundamental economic principles or practices (including hedging, insurance, mitigating risk); commercial or legal interactions (including agreements in the form of contracts; legal obligations; advertising, marketing or sales activities or behaviors; business relations); managing personal behavior or relationships or interactions between people (including social activities, teaching, and following rules or instructions); and

Mental processes — concepts performed in the human mind (including an observation, evaluation, judgment, opinion).

PTO-P-2018-0053, 84(4) Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019) (footnotes omitted).

Claims that do not recite matter that falls within the above groupings should not be considered abstract ideas, except “[i]n the rare circumstance in which a USPTO employee believes a claim limitation that does not fall within the enumerated groupings of abstract ideas should nonetheless be treated as reciting an abstract idea.” Id. at 53.

Is the Claim “Directed To” a Judicial Exception?

The second way in which the Section 101 Guidance revises the USPTO’s previous guidances is to modify the procedure for determining whether a claim is “directed to” a judicial exception under USPTO Step 2A [see above flow chart]. Under this revised procedure:

if a claim recites a judicial exception (a law of nature, a natural phenomenon, or an abstract idea [identification of abstract ideas is described above]), it must then be analyzed to determine whether the recited judicial exception is integrated into a practical application of that exception. A claim is not “directed to” a judicial exception, and thus is patent eligible, if the claim as a whole integrates the recited judicial exception into a practical application of that exception. A claim that integrates a judicial exception into a practical application will apply, rely on, or use the judicial exception in a manner that imposes a meaningful limit on the judicial exception, such that the claim is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the judicial exception.

Id. at 53.

The revised USPTO Step 2A applies to all claims directed to a judicial exception, i.e., claims to an abstract idea, a law of nature or a natural phenomenon. Under the revised procedure, examiners are to evaluate integration into a practical application by: “(a) [i]dentifying whether there are any additional elements recited in the claim beyond the judicial exception(s); and (b) evaluating those additional elements individually and in combination to determine whether they integrate the exception into a practical application.” Id. at 54-55. If the judicial exception is integrated into a practical application, the claim is patent eligible.

To determine whether an additional element (or combination of elements) may have integrated the exception into a practical application, the Section 101 Guidance provides the following non-exhaustive list of examples indicative of whether an additional element (or combination of elements) may have integrated the exception into a practical application, namely, does the additional element:

-

reflect an improvement in the functioning of a computer or an improvement to other technology or technical field;

-

apply or use a judicial exception to effect a particular treatment or prophylaxis for a disease or medical condition;

-

implement a judicial exception with, or use a judicial exception in conjunction with, a particular machine or manufacture that is integral to the claim;

-

effect a transformation or reduction of a particular article to a different state or thing;

-

apply or use the judicial exception in some other meaningful way beyond generally linking the use of the judicial exception to a particular technological environment, such that the claim as a whole is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the exception.

Id. at 55.

The Section 101 Guidance also provides the following examples where an additional element (or combination of elements) has not been integrated into a practical application, namely, does the additional element:

-

merely recite the words “apply it” (or an equivalent) with the judicial exception, or merely include instructions to implement an abstract idea on a computer, or merely uses a computer as a tool to perform an abstract idea;

-

add insignificant extra-solution activity to the judicial exception; or

-

do no more than generally link the use of a judicial exception to a particular technological environment or field of use.

Id. at 55.

As Section 101 Guidance reminds examiners, it is important to consider the entire claim when evaluating whether a judicial exception is meaningfully limited by integration into a practical application of the exception.

The Section 112 Guidance

The second guidance (Section 112 Guidance) will assist USPTO examiners identify issues of indefiniteness, lack of written description and lack of enablement in the examination of patent application claims containing functional language, in particular, claims using functional language to claim computer-implemented inventions.

Examination of Computer-Implemented Functional Claims Having Means-Plus-Function Limitations

35 U.S.C. § 112(f) reads:

(f) Element in claim for a combination. — An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.

The Section 112 Guidance begins by reiterating how examiners should determine whether to apply 35 U.S.C. § 112(f).

Examiners are to apply the “applicable presumption” and the “3-prong analysis” to interpret a computer-implemented functional claim limitation in accordance with 35 U.S.C. § 112 (f), including determining whether the claim includes sufficient structure for performing the recited function. The “applicable presumption” is based on the USPTO’s interpretation of the Federal Circuit’s decision in Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (en banc), and instructs examiners that 35 U.S.C. § 112 (f) is presumed not to apply to a claim limitation that does not use the term “means” or a “generic placeholder” for the term “means.”2 That presumption is overcome when the claim term fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or it recites function without reciting sufficient structure for performing the function. See MPEP 2181(I). The 3-prong analysis is found in MPEP 2181 (I) and instructs examiners to use 35 U.S.C. § 112 (f) when:

(A) the claim limitation uses the term “means” or “step” or a term used as a substitute for “means” that is a generic placeholder (also called a nonce term or a non-structural term having no specific structural meaning) for performing the claimed function; (B) the term “means” or “step” or the generic placeholder is modified by functional language, typically, but not always linked by the transition word “for” (e.g., “means for”) or another linking word or phrase, such as “configured to” or “so that”; and (C) the term “means” or “step” or the generic placeholder is not modified by sufficient structure, material, or acts for performing the claimed function.

PTO-P-2018-0059, 84(4) Fed. Reg. 58 n.3 (Jan. 7, 2019).

The Section 112 Guidance then advises examiners that “[s]pecial purpose computer-implemented 35 U.S.C. 112(f) claim limitations will be indefinite under 35 U.S.C. 112(b) when the specification fails to disclose an algorithm[3] to perform the claimed function.” Id. at 60. A patent applicant cannot avoid the requirement to disclose an algorithm by arguing that a person of ordinary skill would be capable of writing software to convert a general-purpose computer to a special-purpose computer to perform the claimed function. See id.

The Section 112 Guidance also advises examiners that “[s]pecial purpose computer-implemented 35 U.S.C. 112(f) claim limitations are also indefinite under 35 U.S.C. 112(b) when the specification discloses an algorithm but the algorithm is not sufficient to perform the entire claimed function(s).” Id. “The sufficiency of the algorithm is determined in view of what one of ordinary skill in the art would understand as sufficient to define the structure and make the boundaries of the claim understandable.” Id.

Finally, the Section 112 Guidance advises examiners that:

A computer-implemented functional claim may also be indefinite when the 3-prong analysis for determining whether the claim limitation should be interpreted under 35 U.S.C. 112(f) is inconclusive because of ambiguous words in the claim. After taking into consideration the language in the claims, the specification, and how those of ordinary skill in the art would understand the language in the claims in light of the disclosure, the examiner should make a determination regarding whether the words in the claim recite sufficiently definite structure that performs the claimed function. If the applicant disagrees with the examiner’s interpretation of the claim limitation, the applicant has the opportunity during the application process to present arguments, and amend the claim if needed, to clarify whether § 112(f) applies.

Written Description and Enablement of Computer-Implemented Functional Claims

Next, the Section 112 Guidance addresses written description and enablement issues that arise during an examination of computer-implemented functional claims. This section reiterates the standards for written description (i.e., the specification must describe the invention in sufficient detail such that a person of ordinary skill in the art would understand that the applicant had possession of the claimed invention at the time of filing the application) and enablement (i.e., the specification must teach those of ordinary skill in the art how to make and use the full scope of the invention without undue experimentation). The Section 112 Guidance then informs examiners how to apply those standards to computer-implemented inventions.

With respect to the written description for computer-implemented functional claims, due to the interrelationship and interdependence of computer hardware and software, an examiner must evaluate the sufficiency of both the hardware and the software disclosed in the patent application. When evaluating computer-implemented, software-related claims, examiners must determine whether the specification discloses the computer and the algorithm(s) that achieve the claimed function in sufficient detail that one of ordinary skill in the art can reasonably conclude that the inventor possessed the claimed subject matter at the time of filing. “If the specification does not provide a disclosure of the computer and algorithm(s) in sufficient detail to demonstrate to one of ordinary skill in the art that the inventor possessed the invention that achieves the claimed result, a rejection under 35 U.S.C. 112(a) for lack of written description must be made.” Id. at 62.

With respect to enablement, the Section 112 Guidance explains that in view of the high level of skill in the art concerning computer-implemented inventions and the high level of predictability in generating programs to achieve an intended result without undue experimentation, a patent applicant need not disclose what is well known in the art. However, the applicant cannot rely on the knowledge of one skilled in the art to supply information that is required to enable the novel aspects of the invention. Accordingly, examiners must evaluate: “(1) how broad the claim is with respect to the disclosure and (2) whether one skilled in the art could make and use the entire scope of the claimed invention without undue experimentation. … A rejection for lack of enablement must be made when the specification does not enable the full scope of the claim.” Id.

Conclusion

The Section 101 and 112 Guidances strive to improve clarity, consistency, and predictability of actions across the USPTO by providing tools to examiners when examining claims directed to specific categories of inventions. This also provides guidance to patent applicants concerning how the USPTO will prosecute applications directed to those invention categories.